Parsons Cause

Parson's power

The Parsons' Cause was the result of the apostasy of the Anglican Church which was the established church of the colonial government of Virginia. The clergy considered it moral to covet the profits of the people of their perish through men who exercise authority and had accepted the idea that they could be supported by taxes.

In 1748 the salary of a parson was set at 16,000 pounds of tobacco a year by statute. The droughts of 1755 and 1758 caused shortages of tobacco brought on by drought. Laws were like the Two Penny Act were enacted for the purpose of a one year relief from the tax by the same government allowing tobacco obligations to be discharged by the paper money of Virginia.

The one year Two Penny Act allowed the ministers' salaries to be paid at rate of twopence per pound of tobacco which was half of the current market rate which due to the inflation rate of paper money amounted to a third of his tax enforced salary. The colony council, House of Burgesses, and the royal governor approved this temporary relief.

Francis Fauquier, as the royal governor, appealed to Great Britain's Board of Trade and therefor bypassing the Privy Council because there was an immediate need for economic relief. The greedy and immoral clergy argued that they should obtain their pound of flesh at the high tobacco prices and through the efforts of Reverend John Camm of York County and with the help of the Archbishop of Canterbury and the Bishop of London they convinced the king to void the local law and therefore its relief.

The greedy Parsons

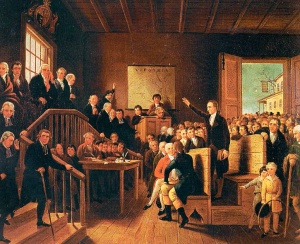

It would be the clergymen suing for back pay the injustice of one court awarding a parson double his normal salary in damages that would bring this matter to a jury in Hanover County and the reasoning of Patrick Henry.

By November of 1763 judge Colonel John Henry had ruled that the Two Penny Act had been null from its beginning likely because to be fully passed into law it should have been approved by the Privy Council in London. This ruling was in conflict with some of the rulings in the earlier cases but it was not in conflict with the terms of the colonial charters.[1]

The damages would be decided by the jury who would hear on one side the lawyer for Reverend Maury.[2] a Peter Lyons and on the other the the young Patrick Henry. Lyons argued the tax would have netted the "good minister" 450 British pounds and he was only asking for 300 which was still double his normal rate of taxation during a time the people all were suffering their own losses from the drought

Maury's gifted lawyer summed up the verdict of the previous month and called two tobacco dealers. They testified that the market price of tobacco averaged 50 shillings per 100 pounds in 1759. At 16,000 pounds of tobacco a year as salary, Lyons computed that Maury had been due 450 British pounds in cash, rather than the approximately 150 pounds he had received under the Two Penny Act. Thus Lyons, after praising the Anglican clergy at some length, asked the jury to award Maury 300 British pounds.

Veto violation or treason

Henry ignored the damages claimed and responded with a one-hour speech, and focused on the unconstitutionality of the veto of the Two Penny Act by the king's government.

Patrick Henry argued that to veto a good laws the king forfeited his right to the obedience of his subjects because he abandoned his obligation to protect the people. Instead of being a "father" to his people, he "degenerates into a Tyrant." Lyons, who was not alone in his thinking in the courtroom, accused Henry of speaking "treason".

Harpies, widows and the Jury

Henry made his own accusations against the clergy, "Do they feed the hungry and clothe the naked? Oh, no, gentlemen! These rapacious harpies would, were their power equal to their will, snatch from the hearth of their honest parishioner his last hoe-cake, from the widow and her orphan children her last mich cow! the last bed-nay, the last blanket-from the lying-in woman!" Patrick Henry wanted the jury to award only a single farthing but after deliberating only five minutes they granted the poor preacher four times that amount which was only one penny.

A little more than a decade later Jefferson would refer to the many acts of the King as unwarranted usurpations.[3]

Footnotes

- ↑ "At first, it was nearly impossible to find settlers to colonize this new land until the signing of the colonial charters by Charles I, and eventually Charles II, which waived rights of the kings of England that had inhabited Great Britain... In those charters, the individual colonies were called “a republic”... refuges of individual responsibility where no law could be made “except by the consent of the freeman”." The Covenants of the gods.

- ↑ Reverend James Maury filed suit for their levied back pay which the Two Penny Act had given some relief. Some clergy wanted to be paid in currency at a fixed rate of two pence per pound of tobacco. When the act was vetoed by the king some clergy wanted to get what they had coming at the higher rate.

- ↑ From the book The Covenants of the gods: "Even before the so-called American Revolution, the united States found that, “Natural law was the first defense of colonial liberty”. Also, “There was a secondary line upon which much skirmishing took place and which some Americans regarded as the main field of battle. The colonial charters seemed to offer an impregnable defense against abuses of parliamentary power because they were supposed to be compacts between the king and people of the colonies; which, while confirming royal authority in America, denied by implication the right of Parliament to intervene in colonial affairs. Charters were grants of the king and made no mention of the parliament. They were even thought to hold good against the King, for it was believed that the King derived all the power he enjoyed in the colonies from the compacts he had made with the settlers. Some colonists went so far to claim that they were granted by the ‘King of Kings’-and therefore ‘no earthly Potentate can take them away.’” Origins of the American Revolution, By John C. Miller. Published by Stanford University Press, 1959. And The Other Side of the Question: or A Defence of the Liberties of North America. In answer to a ... Friendly address to all reasonable Americans, on the subject of our political confusions. By a Citizen, New York, 1774, J. Rivington, 16. Bulletin of the New York Public Library. By New York Public Library.